A Ghost Story?

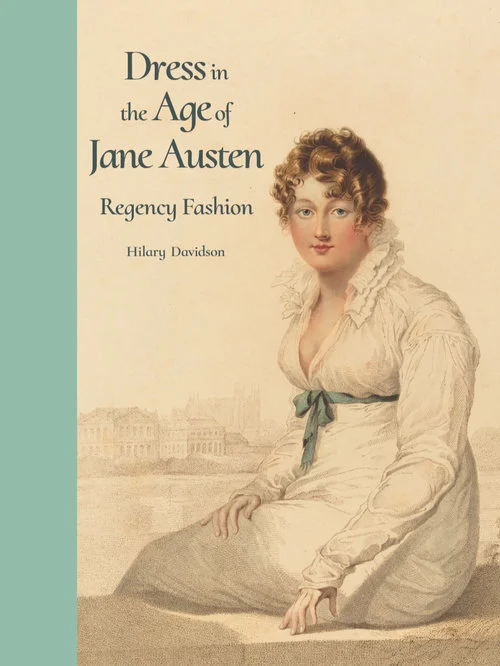

In November 2019, I had the honour of launching Hilary Davidson’s beautiful book, Dress in the Age of Jane Austen, at the Johnston Collection in East Melbourne.

The world was, of course, about to plummet into the pandemic crisis (how blithely I went out afterwards with a friend to drink a whiskey sour at Buck Mulligan’s on High Street!) and so I hold on to this remembered moment. The quiet room, the evening sunshine outside, the city gardens.

Looking over my words in preparation for posting them here, the occasion came back to me strongly, inevitably inflected with nostalgia for the time when we did not know. I hope I did Hilary’s achievement justice.

Speech to launch Dress in the Age of Jane Austen, 19 November 2019, East Melbourne

I’m going to begin with a ghost story, if I may.

Once upon a time, a Jane Austen scholar was alone in her university office, pondering the position of a comma in the 1814 edition of Mansfield Park. Claudia Johnson now takes up her story:

Again and again, I read the two sentences aloud quietly to myself ... until, finally, under these inauspiciously pedantic circumstances, a startling thing happened: I heard Jane Austen breathe.

As I read and reread those passages, I heard a clear intake of breath, and I reeled around in my chair to see if anyone had quietly slipped into my office. The respiration, I realized immediately … seemed very important at that particular moment, for in older practice, still in force when Austen wrote, a comma … indicated a pause during which a reader was to breathe.

Was it Jane Austen returning to tell her where to place the comma? I hope so. Who knows?

But I start this way because Hilary also carries out a feat of revenance, in this remarkable book that we have before us this evening. Hilary’s words restore Jane Austen to her body, her breathing body, her clothed body, and show it moving around amongst other clothed bodies – in homes, in streets, in shops. And these bodies, in turn, were also moving about in a country, and around a globe. All in an age animated by books and print and movement and ideas, and transformed by military and naval might; criss-crossed by oceanic travel that established international trade networks and shifted global power, delivering and enforcing brutal domination to some; and bringing sugar and muslins and Indian shawls and Mansfield Parks to others.

Hilary’s book encompasses a world of bodies and ideas and things. Its chapters move - and I’m going to give in to my almost overwhelming urge to use textile metaphors, and say ‘the chapters move seamlessly’ - from underwear to mourning dress to riding gear to evening wear to military uniforms, and many other items besides. These chapters take the reader from the home to the shop, from the village to the city, from the nation to the world.

Dress in the Age of Jane Austen employs the tools of a whole range of scholarly approaches. Hilary writes with the historian’s comprehension of chronology, identifying the patterns which emerge across time and space; and the with the archaeologist’s forensic attention to detail, in order to uncover the layers of meaning that reside in places and objects. She also takes up the literary scholar’s toolkit, using close reading to coax out what lies within paragraphs and sentences and words. And, most of all, she builds a powerful study of the material culture of the Regency period, bringing alive the tangible realities of life, and death, in the past.

Jane Austen is in this book’s title, and everywhere in its pages. Hilary uses Austen’s ‘defined middling-gentry world’ to explore wider questions, asking how ‘the microcosm of dress’ in that world, relates to other concerns and trends. It constantly travels from the particular, our Jane, to the more general, and then back again, all rendered in exquisite, finely-stitched, detail.

Jane Austen is at the heart of this book. We see her reconstructed pelisse, the culmination of Hilary’s groundbreaking research and replica work; we spend time with her in the homes in which she lived across the all-too-short span of her life; we read excerpts from her letters, which show, in Hilary’s words that ‘Austen despaired of and delighted in the niceties of getting and wearing dress as much as the next person’. Hilary tops and tails the prevailing images of Austen by highlighting the prevalence of hat and bonnet talk in Austen’s correspondence, and reminding us of her need for pattens, raised wooden platforms, when she walked in the muddy country roads around Chawton. (And every reader of Pride and Prejudice knows of the perils of mud for feisty women).

Biographical details of Austen’s life are contextualised in this book in ways that greatly enhance understanding of the life and times of this much beloved writer, and particularly its fashion and dress cultures. The book also contributes to literary studies, and Austen scholarship, in its extensive and judicious referencing of Austen’s novels. Integrated into its argument, we find enlightening discussions of genteel walking in Emma and Sense and Sensibility, and are alerted to the sartorial dimension of Henry Crawford’s faux pas in Mansfield Park, when he speaks with a girl ‘not out’. We see Elizabeth Bennet at her needlework, an everyday task whose regularity, Hilary comments, ‘keeps her mind free to watch interchanges between Mr Darcy and Caroline Bingley that are key to the later plot’. Such moments bring new ways of reading Austen’s familiar novels.

This book is meticulously researched and referenced, and its pleasures are also visual. This is scholarship in full dress. It is richly and generously illustrated with images from art and portraiture, and nineteenth-century journals and fashion plates, photographs of shoes, gloves, dresses and shirts, (and you can see a photo the famous pelisse there), a cutting diagram for a man’s shirt from 1808, and samples of British merino products, just to name a few.

Through word and image, this book manoeuvres dextrously between Austen’s life and work and world. Dress in the Age of Jane Austen, like its author, is intelligent and elegant, and I am delighted and honoured to commend it to you, and to declare it launched into a waiting, and material, world.

https://yalebooks.yale.edu/book/9780300218725/dress-age-jane-austen